Tension Measurement & Monitoring Devices

Tension measurement and monitoring devices are absolutely critical in power line stringing and maintenance. Maintaining precise tension is fundamental for:

Safety: Preventing overstressing conductors and equipment, which could lead to failures.

Structural Integrity: Ensuring towers and poles are not subjected to excessive loads.

Electrical Performance: Achieving the correct sag and clearance, which is vital for maintaining required ground clearances, phase-to-phase clearances, and preventing excessive blow-out under wind/ice loads.

Long-Term Reliability: Reducing fatigue on conductors and fittings, extending the life of the line.

Compliance: Meeting design specifications and regulatory requirements.

Here's a breakdown of common tension measurement and monitoring devices:

1. Dynamometers (Load Cells)

Dynamometers are the primary devices for directly measuring tension (force) in pulling ropes, pilot wires, or conductors during stringing. They convert mechanical force into a measurable signal.

a) Hydraulic Dynamometers:

Principle: Operate on the principle of hydraulic pressure. A piston or diaphragm is acted upon by the tension force, which in turn pressurizes hydraulic fluid. This pressure is then displayed on a calibrated gauge.

Advantages:

Simple, robust, and reliable.

No external power source required (fully mechanical display).

Excellent for use in harsh environments.

Typically less expensive than electronic equivalents for similar capacities.

Disadvantages:

Less precise than electronic dynamometers.

No data logging capabilities (unless paired with an external sensor).

Can be affected by temperature changes (though designed to minimize this).

Applications: Commonly used on tensioners and pullers (often integrated) or inserted directly into the pulling line during stringing.

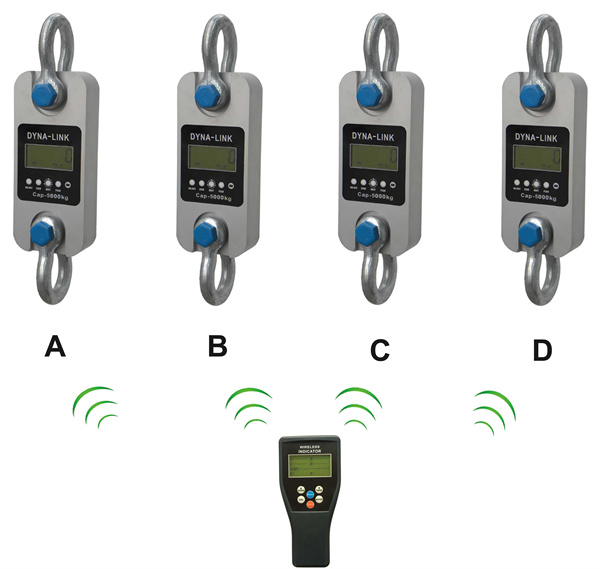

b) Electronic Dynamometers (Digital Dynamometers / Load Cells):

Principle: Utilize strain gauges (transducers) that change electrical resistance when subjected to mechanical strain (force). This change is converted into an electrical signal, amplified, and displayed digitally.

Advantages:

Highly accurate and precise readings.

Digital display for easy reading.

Often include advanced features: peak hold, tare, units conversion (kN, kg, lbs), overload alarms.

Data logging capability: Can store readings, transfer data to computers/smart devices via USB, Bluetooth, or Wi-Fi for analysis, trending, and record-keeping.

Can be integrated into more complex monitoring systems.

Disadvantages:

Require a power source (batteries or external supply).

Can be more sensitive to electromagnetic interference (EMI) or environmental factors if not properly shielded/ruggedized.

Generally more expensive than hydraulic models.

Applications: Integrated into tensioners and pullers, attached directly to pulling lines or conductors, used for proof-testing, and for precise sag and tension adjustments.

Types of Dynamometers based on form factor:

Inline (Shackle-Type / Link-Type) Dynamometers: Shaped like a shackle or a link, they are inserted directly into the pulling line between the pulling equipment and the conductor/pulling rope.

Running Line Tensiometers (RLT / Running Line Monitors): These are specialized, multi-sheave devices through which a moving wire or rope passes. They continuously measure the tension in the moving line, and often also measure line speed and length. Essential for large-scale stringing, offshore cable laying, and crane operations. (As seen from Crosby|Straightpoint and Strainstall in search results).

2. Line Tension Meters (for in-situ measurement)

These devices are designed to measure tension in an already installed or stationary wire or cable, typically without breaking the line.

Principle: Most operate by deflecting the wire a small, known amount and measuring the force required for that deflection, or by measuring the deflection caused by a known force.

Advantages:

Non-destructive measurement.

Portable and easy to use in the field.

Useful for auditing sag, checking tension during maintenance, or verifying initial stringing.

Types:

Mechanical (Analog) Meters: Simple, often pointer-type gauges.

Digital (Electronic) Meters: Offer higher accuracy, digital display, and sometimes data logging.

Applications: Checking guy wire tension, overhead line sag/tension verification, and tension in smaller communication or fiber optic cables.

3. Integrated Tension Monitoring Systems

Modern tensioners and pullers often come with integrated load-indicating and load-limiting devices. These systems continuously monitor the pulling/tensioning force and display it to the operator. Some advanced systems can:

Preset Max Pull/Tension: Automatically stop the operation if a preset limit is exceeded.

Record Data: Log tension profiles over the entire stringing operation.

Communicate: Interface with other equipment or control centers.